How to limit the impact of “Grass is always greener syndrome” by closing some doors

We have never lived in a more free world than today. Unlimited options and life possibilities wherever you look. Do you also find yourself ruminating many of them, not being able to decide? This is a new age problem, part of the “grass is always greener on the other side” family and this post is about how you can limit its effect.

This post is inspired by Dan Ariely’s book “Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions” which is a great insight into our numerous biases that are actually very common and predictable. The author illustrates all our predictably irrational behaviours in a series of tests and trials he produced throughout his career as a cognitive psychologist.

Having options is good, it’s how you handle them

There is nothing wrong with having all the options available to us now. We can travel around the world freely, we can say what we want, do what we want, believe in whatever we want and live our lives mostly the way we want.

The trouble arises not from these options, but from our inability to choose between then and to know what is exactly what we want. And even if we figure it out eventually – we find it hard to stick with that decision. Let’s take a look at what are the drivers behind it. Because you can only control what you know – if you’re aware of certain bias, you will start noticing it and this is the path towards managing it.

Biases and fallacies that feed the Grass is greener syndrome

Easy comparison

“We not only tend to compare things with one another but also tend to focus on comparing things that are easily comparable—and avoid comparing things that cannot be compared easily”

Dan Ariely – Predictably Irrational

What does this say about our ability to choose? According to Dan Ariely, if something is easy to compare, we tend to do it. Our brains are wired like this. The trouble is that if presented with too many options that are easy to compare, we get overwhelmed and stuck in a comparison race. It’s hard enough when choosing a TV, but what about our lives?

Consider the number of role models and successful people we are bombarded with through social media (we choose to follow) or TV. They look great, have great spouses, plenty of wealth. But do they? We never see the background – there isn’t a specifications comparison option for humans. We only see the good, the bad is hidden.

Easy to compare? The second trouble here is how easy it is to compare ourselves to such social media “role models”. We know every dirty detail about ourselves – how often we are lazy, procrastinate, what bad decisions we made and how apparently mundane our daily routine is. Then we see the exciting life of Instagram influencers through the lens of their “post only what’s good for marketing” filter. We don’t realise that they also have a mundane daily routine, that 3 photos per day don’t make a whole day, that they also have to go shopping, do taxes or sit in front of the TV sometimes.

The paradox of choice

Having more options means we spend more time choosing between them and have less time to enjoy the choices we have already made.

The Paradox of Choice is a modern phenomenon – arising from the improvement in connectivity, internet, availability of goods and wrong values promoted by the media (wealth, bling etc.).

If you want to dive deeper into the Paradox of Choice, I recommend David Schwartz’s book “The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less“

This problem is compounded by the fact that if we are presented with so many options, even if we end up choosing, we then look back and can’t stop thinking, whether that was the right choice. Ever bought a phone just to see a friend’s phone with slightly different specs and thought to yourself it seems better than yours?

Loss aversion

..avoiding temptation altogether is easier than overcoming it.

Dan Ariely – Predictably Irrational

This sounds like a piece of good advice, right? We all agree with it, true? Of course we do. Yet we are almost unable to follow it. Why is that?

Most of our decisions aren’t based on a calculated rational analysis, but on our emotional state at the time of the decision, our biases and habits. One such bias is loss aversion – we prefer to avoid a loss to acquiring an equivalent gain (i.e. you feel stronger about losing 5 USD then about finding 5 USD on the floor). We are not very willing to change bad habits out of fear, that this change might result in a worse situation than before. And this keeps us stuck in a rut. We just don’t like to lose stuff we consider our own. Be it people, habits or material things (that’s why some people stay in dysfunctional relationships, hoard stuff in their life just to become slaves of it, or can’t let go of bad habits) – or be it our options.

That’s why we find it very hard to surrender some of our options – or “closing some doors” according to Dan Ariely:

We are continually reminded that we can do anything and be anything we want to be. The problem is in living up to this dream. We must develop ourselves in every way possible; must taste every aspect of life; must make sure that of the 1,000 things to see before dying, we have not stopped at number 999. But then comes a problem—are we spreading ourselves too thin?

Dan Ariely – Predictably Irrational (requoted from Erich Fromm’s research)

And you can probably guess, what the answer to that question is. We are spreading ourselves too thin and on top of that, we find it hard to let go of dreaming about living in another country or maybe trying a different career, or perhaps a partner?

Hey, there’s a newer term for that – FOMO (fear of missing out). Just 100 years ago, people didn’t have so many options. So their fear of missing out included a much narrower range of things. But today, anything is possible if you try really, really hard enough. And with the growth of possibilities grows our FOMO. There’s much more to miss out on – theoretically. But practically, it hasn’t changed much – you can’t try it all out. So stop trying and you’ll be happier.

The correct option (mathematically, financially and emotionally) is limiting the number of doors we consider as our options. Here’s, for example, what might help with “grass is always greener” thinking in relationships:

ALBERT (a test subject) HAD CONFIRMED something that we suspected about human behavior: given a simple setup and a clear goal (in this case, to make money), all of us are quite adept at pursuing the source of our satisfaction. If you were to express this experiment in terms of dating, Albert had essentially sampled one date, tried another, and even had a fling with a third. But after he had tried the rest, he went back to the best—and that’s where he stayed for the remainder of the game.

Dan Ariely – Predictably Irrational

We are basically trying to lower our opportunity cost – “the loss of potential gain from other alternatives when one alternative is chosen”. The trouble with this is that we can never know the real opportunity cost – the options are too many to calculate that. Thinking you can limit your opportunity cost in life by keeping more options open is a fallacy. It might work in environments with clearer variables and fewer options to choose from (finance, choosing between a smaller number of products), but it doesn’t work in life situations involving endless opportunities.

Solution: whether it’s choosing between life partners or investments – it’s always better to sample a few, then choose the one that meets most of your criteria and stick with that choice, rather than to always keep a backdoor open. That nagging feeling will never go away, you will be less happy. But the irony is that even if you tried to sample hundreds of more choices, you’d still end up equally unhappy because there would be thousands more you haven’t tried.

Advice from Dan Ariely:

In fact, in their frenzy to keep doors from shutting, our participants ended up making substantially less money (about 15 percent less) than the participants who didn’t have to deal with closing doors. The truth is that they could have made more money by picking a room—any room—and merely staying there for the whole experiment! (Think about that in terms of your life or career.)

Dan Ariely – Predictably Irrational

Negativity bias

Combine this with the negativity bias and we have a good recipe for gloomy days. Our negativity bias means that we feel stronger emotions about negative / unpleasant thoughts, emotions than their equally intensive positive counterparts.

In other words, something very positive will generally have less of an impact on a person’s behavior and cognition than something equally emotional but negative.

Wikipedia

Translated into the context of this article – this means that your doubts will feel “heavier” than any positive thoughts you will produce. Note the emphasis on “feel” – they are not heavier. They just feel that way, your biased brain serves it that way.

Solution: When having negative thoughts, acknowledge them, but don’t let them linger. Remember that they will feel heavier than they actually are. List out positive things in the same situation and try to dwell on those instead. Can you build on those positive feelings? Can you find some more or extend them?

Regression toward the mean / Habituation / Hedonic treadmill

These three tendencies are observed in various areas of life (math, statistics, behaviour) and represent a similar effect, which in the context of this post translates into:

Whatever you have in your daily routine becomes the new standard. Even the great things you wanted to achieve will suddenly lose their appeal and become just average.

According to this theory [hedonic treadmill], as a person makes more money, expectations and desires rise in tandem, which results in no permanent gain in happiness.

Wikipedia

We can easily replace “makes more money” in the above statement, with achieving whatever else our hearts desire – love, sex, a bigger house, more opportunities, better view, nicer body…

We should also pay particular attention to the first decision we make in what is going to be a long stream of decisions (about clothing, food, etc.).

Dan Ariely – Predictably Irrational

Because once you buy a better car, you are not going to buy a cheaper one a few years down the line. Once you buy a 1000 USD phone, you will feel weird buying a 400 USD phone after that. Be careful what stepping stones you choose for yourself. You can use this to your advantage too – when it comes to material stuff – always choose the lowest viable option for you (what specs you really need, without the additional “hmm, this is interesting” features), and make the next step (upgrade) a very small step.

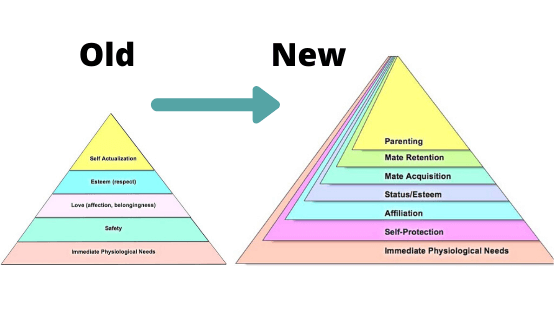

Look into nature – all living things, except humans, seem to be content with the bottom layers of Maslow’s pyramid – food, shelter, procreation. Only humans need more and more layers at the top. That’s ok, we have very different brains and abstract thinking abilities to the rest of living things, but we should be aware of all the downfalls of this capacity too.

I tried both in my life – complete freedom (travelled the world for 3 years, lived freely, without commitments and … eventually, it lost its appeal and I started craving a solid base and a relationship – which was amazing when I found it, but became harder work later and sometimes I crave the freedom again. But I know that this cycle would never end. And there’s one thing I haven’t tried yet – sticking to a relationship for decades, working on it and creating a life together. That’s something new I’m exploring and although it’s hard work sometimes, it has many benefits too :).

I also came to the conclusion that humans seem to be the happiest when they can choose the pyramid levels freely – balance them depending on their need. One day you feel like conquering the world and desire self-actualisation. But another day you feel like shelter, (junk) food and comfort is all that’s needed. Balance seems to be key to our happiness. You want affection, but you sometimes want a break from affection (if it’s there when you don’t seek it). You want self-actualisation, but only when you feel like it, you don’t want it to become a responsibility – a burden. What you really want then, is to be able to freely move between these layers.

If this notion interests you, check out Professor’s Douglas T. Kenrick’s research “Renovating the Pyramid of Needs: Contemporary Extensions Built Upon Ancient Foundations” discusses the idea of a more dynamic Maslow’s pyramid in-depth – and proposes an updated pyramid diagram:

Solution: be aware that whatever you desire today, will become routine in the future. Whatever seems cool and exciting and sexy will become your average in the future. That’s ok – if you’re aware of it, you will know that although your lizard brain will see many more exciting, sexy or lucrative options, your intelligent brain, the prefrontal cortex will know that it’s just an illusion, a race you can’t win. Reflect back onto Maslow’s pyramid of needs – do you have them covered? Maybe all that’s missing is just selecting a different layer of the pyramid, to focus on for a while.

Herd mentality

When individuals are affected by mob mentality, they may make different decisions than they would have individually.

Wikipedia

We are a social animal and our brains have adapted accordingly. It makes sense to conform with the majority (the herd) to increase our chances of survival (success in today’s terms perhaps). This evolutionary adaptation is good most of the time, but sometimes misfires.

When we forget about this bias of ours, we start thinking, that whatever the majority does, must be right. If all of them have 4 cars per 3 family members, then we feel entitled to have the same. If everyone else is buying stuff they don’t need, why shouldn’t we? If celebrities have a different partner every year, why shouldn’t we?

The problem with this thinking is basing/rationalising one’s needs according to external factors, not our actual needs. Do you need two cars to live your life, or do you just desire a second, because you can? Entitlement might be ok, something that drives you forward, that pulls you out of a mundane routine. But careful it doesn’t become psychological entitlement.

Solution: always ask yourself whether there’s a direct internal (your) need for this longing, or it’s merely based on entitlement or external observation (if they can, I can). Learning to lower your expectations to only your internal and more basic needs will save you a lot of money (by not buying many pointless material things), save you a lot of stress (working harder to get money for all that buying) and anxiety (you will always find someone, who has more than you – it will never end).

Conclusion

As you can see, there are many psychological fallacies and biases that we are born with. The list goes on and on, this article is far from exhaustive – but it should serve well enough to paint the picture: the only way to be happier is to know yourself (and your fallacies) and learn to control them by limiting their impact. Many of these fallacies revolve around the same issue – we think we need more than we actually do.

You might have noticed a phrase that repeats itself here: “it never ends”. For a brain that was shaped on a very simple life (sleep, food, run away from danger, sleep, food, fornicate, sleep, food), we have created a society of never-ending possibilities. That’s good – if only our lizard brains could adapt that fast – but they can’t. Therefore, to live a more balanced and happier life – design your life to have less possibilities and distractions, focus on your direct, internal and more basic needs and don’t be afraid to close some doors. Choose a few options for each layer of the pyramid of needs, work on them and don’t worry about any other options anymore.

Everything in nature is very complex – every organism or matter. But it all works just fine with only a few basic needs and rules that govern it all. Shouldn’t it work the same way in our lives too? And if not – what does it say then, about the pinnacle of evolution, the human brain – that can, for example, eat itself to death by not being able to control its impulses?